Chasing the Matterhorn

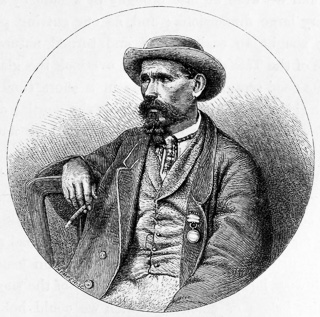

The Swiss alpine guide from Zermatt was born in 1820. He lived above Zermatt with his four sons. He survived the Matterhorn's first climb. However, in the aftermath of the first ascent he had to face years of public criticism: The public suspected him of bearing responsibility for his comrades' deadly fall. Talk of the town went like he cut himself off the rope that held him and his fellow climbers together to save his own life. Taugwalder took this criticism to the grave, since the rope cutting theory was only rejected after his death. He died in 1888 above Zermatt. The town's municipality dedicated Taugwalder a memorial posthumously.

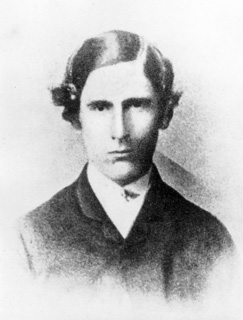

Edward Whymper was born in 1840 in London to penniless parents. The landscape painter came to the Alps in 1860. He developed a passion for first ascents and also was part of the Matterhorn's first climbers. After the accident he had to face plenty of criticism until the end of his life. He died in 1911 in Chamonix.

Alpine guide and stonemason from the Valtournenche region. Member of the Matterhorn's first climbers via the Lion's ridge. From early on Carrel belonged to the few convinced that the Matterhorn could be scaled. After having climbed the Matterhorn, Edward Whymper and Carrel went on to scale mountains in South America. For instance, they mastered the first ascent of the Chimborazo. During his life time, Carrel climbed the Matterhorn 53 times. He died from fatigue in 1890 at the Lion's ridge.

Still in his childhood, Peter Taugwalder junior already trained scaling mountains under oversight of his father. He was part of the Matterhorn's first climbers, being only 22 years old. He survived his comrades' fall and successfully launched an alpine guide's career later in life. He got married twice, had 12 children and died in 1923 at the age of 80.

Francis Douglas was a Scottish nobleman and a famous member of the London Alpine Club. He died in the accident at the Hörnli ridge. His body was never found.

Born in Chamonix, Michel-Auguste Croz was famed as one of the most successful climbers and alpine guides of the 19th Century. He was part of the Matterhorn's first climbers. He died in the accident at the Hörnli ridge.

Born in England in 1828, Hudson was an Anglican priest. He was dealt one of the best climbers of his times. For instance, he mastered to climb the Montblanc without a guide. He died in the accident at the Matterhorn.

With only little experience the English man was the weakest climber during the Matterhorn's first ascent. Furthermore, being only 19 years old, he was the youngest of the group. Hadow died in the accident. In the accident's aftermath Hadow's misstep and slipping were dealt as the cause of his and his comrades' fall.

THE MOUNTAIN

The Matterhorn was the last big challenge of the Alps. For a long time the distinctive rock pyramid on the Swiss-Italian border was thought to be impossible to ascend. The mountain seemed far too steep from the valley, its ridge too narrow. In the second half of the 19th century one mountain giant after another had been conquered. But the Matterhorn remained undefeated. Adventurers from all over the world strived to claim this trophy. Only local Swiss mountain guides avoided the Matterhorn, or “Hore” (Swiss dialect for “horn”), as the Zermatters call it: Tales of evil spirits who would punish anyone brave enough to set foot on the mountain’s rocks were told among the native Zermatt population.

Jules Beck / Alpines Museum der Schweiz

But Jean-Antoine Carrel, a stonemason and mountain guide from Cervinia, an Italian village situated on the south face of the mountain, was convinced that he could reach the summit. From 1858 onwards the Italian tried to climb the Matterhorn multiple times. It was not only him trying. On the Swiss side, mountain farmer and guide Peter Taugwalder estimated an ascent via the Hörnli ridge, from the north, would be possible. The years between 1840 and 1865 should later be known as the golden age of alpinism. Adventurous Englishmen discovered the Alps as their new playground and thus most advanced the conquest of the peaks. From 1855 onwards, all substantial first climbs were conducted by the British. The London Alpine Club – the world’s first mountain sport association – subsidised them.

Getty Images

Summiteers from Great Britain

In 1860, a certain Edward Whymper travelled to Zermatt on his editor’s request. The 20-year-old painter and engraver from London crafted alpine landscape paintings, which were immensely popular at the time. The young Englishman quickly found a worthy purpose of his ambition in the mountain peaks. From the very start he was interested in participating in summit attempts even though he lacked any alpinist knowledge. But Whymper was tough and athletic. He was not interested as much in experiencing nature as he was in the challenge. He wanted the trophy.

PD

Edward Whymper managed to gain Italian mountain guide Carrel for a joint first summit attempt on the Matterhorn. In the years 1862 and 1863 they went on three climbs once surpassing the 4,000-metre mark. Whymper admired Carrel and the latter respected his English client. But they remained competitors, even though they shared the same goal for years.

"I have known Jean-Antoine Carrel for the last eight years and consider him the finest rock climber I have seen. He possesses the highest courage and whether for one who wishes to make difficult excursions, or for one who wishes to make ordinary ones, he will be found a first rate guide."

Until 1863 Whymper set off at least seven times to reach the Matterhorn’s summit. Time and time again he was forced to return due to bad weather or his lack of experience and skill. But he was not the only one. Another Englishman had come closer in reaching the Matterhorn’s 4,478 metre peak: John Tyndall reached 4,258 metres on the southwest shoulder climbing over the Lion ridge. The spot is known as Pic Tyndall today.

In the summer of 1865, a victory was finally to be enforced on the Matterhorn. Swiss and Italians strived for it, and of course the English, most notoriously Whymper. The Italian Club Alpino provided material and prepared a “major offensive” lead by Jean-Antoine Carrel. Once again Whymper crossed the Theodul Glacier on the way to Cervinia. In the previous winter he had managed to conduct two significant first ascents: the western peak of the Grandes Jorasses and the Aiguille Verte.

Whymper now plans to win over Carrel for a new attempt at the Matterhorn. But the mountain guide is nowhere to be found: Carrel left for the Lion ridge with a rope team without Whymper. Although possible agreements between Carrel and Whymper are no longer retraceable, it seems clear that the Italian was eager to get rid of the overambitious Englishman. Whymper realizes: the race to the summit of the Matterhorn has officially begun. The British climber finds himself in Cervinia with a lot of baggage but without a guide and a companion. Quitting? He does not think about it for even one minute. He will now have to try it without Carrel and from Zermatt.

One of Many Coincidences

In this situation one of the many coincidences that constitute the incredibility of this first ascent occurs: On July 11th 1865 at noontime Whymper runs into young Lord Francis Douglas by chance. A fellow member of the London Alpine Club, Douglas, proposes to hire Peter Taugwalder when hearing about Whymper’s plans. Then they meet Taugwalder at his house, located on the way to Zermatt, and he agrees. Faced with two guests, Taugwalder insists on hiring a second mountain guide and decides to bring his two sons along as carriers.

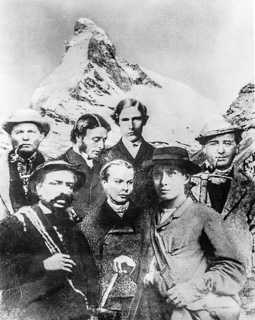

On the evening of July 12th, Reverend Charles Hudson arrives alongside renowned Chamonix mountain guide Michel Croz at the Zermatt Hotel Monte Rosa. Hudson is one of the most significant and capable alpinists of his time. Whymper is at the Hotel, too. As Hudson also happens to plan to climb the Matterhorn via the Hörnli ridge the next day, the men decide to join their efforts. In spite of Whymper’s skepticism, Hudson insists on bringing relatively inexperienced 19-year-old Briton Douglas Hadow along. Thus within less than 48 hours, a random group of people emerges. Even though they have never climbed together before, they still have every intention of reaching the most difficult of all summits at this time: the Matterhorn.

Zermatt Tourismus

THE ASCENT

July 13th, 5 a.m.After having hastily packed the most important things the night before, the eight pioneers leave Zermatt in the morning. Restlessly driven 25-year-old Edward Whymper leads the group. He wants to beat rival Jean-Antoine Carrel on the other side of the mountain. Without much trouble the climbers reach the Schwarzsee, a lake up on 2,583 metres, where they left behind some of their material the day before. They now carry three safety ropes: two strong specimens newly developed by the Alpine Club and one thinner rope.

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Old Peter Taugwalder sends his youngest son back to Zermatt, while he appoints his older son, 22-year-old Peter Taugwalder, to serve as mountain guide. In order to distinguish Peter junior from his father, most authors refer to the two mountain guides as young Peter and old Peter. The four Englishmen, the Frenchman and the two Swiss continue their climb on the Northeast ridge, which joins the Hörnli ridge and the Matterhorn. The group of seven reaches the foot of the mountain and continues their ascent up to 3,300 meters.

July 13th, 12 p.m. Slightly above today’s Hörnli hut, the group takes a break and sets up the tents for the night. Meanwhile on the Italian side Jean-Antoine Carrel and his three companions are much further along on this same day. With a two-day lead over the Zermatt rope team they have crossed the Col de Lion and reached the so-called Grand Tour at 3,889 metres. Here the Italian pioneers rest, eat some of their provisions and set up camp unaware of their competitors on the other side of the Matterhorn.

July 14th, 3:40 a.m. Because of its free stand and exposure to the wind, the Matterhorn is often shrouded with clouds, even in clear weather. But on this early morning in 1865, this is not the case. The sky above the Valais Alps is without a single cloud as the seven climbers start their climb on the Hörnli ridge before sunrise. Edward Whymper knows: if his group keeps up a steady pace today, they can overtake Carrel.

July 14th, 6 a.m. Jean-Antoine Carrel and his men get up much later and therefore already have the cards stacked against them in the race to the peak. Around the same time Whymper, the Taugwalders, Douglas, Hudson and Hadow take their first break at a height of 3,900 metres. Soon after they pass the place where the Solvay hut, an emergency shelter, stands today.

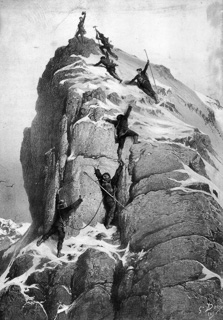

July 14th, 10 a.m. Whymper’s group reaches the peak rock’s foot at 4,260 metres. So far the seven climbed without the help of their ropes. But now the terrain becomes steeper and more difficult. The interstices of the rock face are filled with snow, and the rocks are often covered in ice. The seven mountaineers rope up and Michel Croz, the Chamonix mountain guide, leads the team. Suddenly the ascent turns into steep rock climbing. Regarding their equipment, their enterprise was more than precarious from today’s point of view. Especially 19-year-old Douglas Hadow is struggling. His shoes are slippery, since they lack nails in the soles. In addition, this is his first real rock climbing experience.

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

July 14th, 11:40 a.m. In an attempt to avoid a steep place in the ridge, the rope team scales the much more difficult north face. They lose valuable time: For a short traverse the group needs one and a half hours. Until today the easiest route remains the one on the ridge.

July 14th, 1:10 p.m. Then, sudden relief: a relatively flat snowfield unfolds in front of them. They have overcome all difficulties, and the peak is near. They are so close to the finish that Edward Whymper as well as Michel Croz can no longer pull themselves together: they untie themselves from the rope and start to run towards the summit.

"The slope eased off, at length we could be detached, and Croz and I, dashing away, ran a neck-and-neck race, which ended in a dead heat."

July 14th, 1:40 p.m. Whymper is the first to reach the Matterhorn’s summit, followed by Croz. Together they gaze down on Zermatt and over the Valais Alps all the way to the Montblanc.

The summit was theirs; the last 4'000-thousand-metre peak of the Alps had been conquered. Reverend Hudson, Lord Douglas, Douglas Hadow and the two Taugwalders also reach the summit. To make sure that the Italians had not beat them to it after all, Whymper and Croz pass the flat 100-metre long ridge and walk to the summit’s Italian side. They spot Jean-Antoine Carrel and his three men on the Lion ridge at 4,230 metres. To gain their attention the Englishman shouts and throws stones down the mountain. Carrel acknowledges his defeat. The Italians made it as far as Pic Tyndall. It is uncertain if Carrel was still ascending at this time or whether he had initiated the descent due to problems. But Whymper only won by an inch. For Carrel it must have been very disappointing.

PD

July 14th, 2 p.m. While Carrel and his group turn around disappointedly, the first climbers build a cairn and raise a flag (Croz’ blue blouse) on top of the Swiss summit. The rest on the top is a long one – the men enjoy their triumph. But the ascent is always only half the way. As Whymper later reports, he and Hudson discussed the order in which they then descend together.

July 14th, 2:45 p.m. The most experienced mountaineer Croz descends first, followed by Hadow, the weakest link of the rope team, Hudson and Lord Douglas. The four men are connected by one of the strong Alpine Club ropes. When Whymper notices that no one left their names on the summit, he doubles back and deposits a bottle with a note in it. Upon his return to the group, he ties himself to young Peter, the last of the party. When they reach the most difficult part of the descent, Douglas asks Whymper to tie onto old Peter. He fears they will not be able to hold ground and secure Hadow, should a slip occur. Old Peter ties himself to Douglas using part of the thinner rope, as he later relates. The stronger rope’s remaining end was too short to use. Now they are one long rope party of seven again. They slowly move down the steep north face in tense silence. One at a time moves while the others secure him.

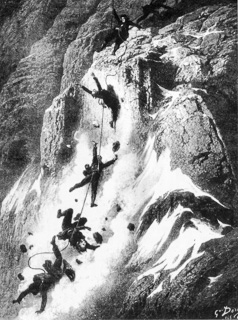

July 14th, 3 p.m. Clumsily climbing Hadow needs continual assistance: Croz uses his hands to put Hadow’s feet into the steps. As old Peter Taugwalder and Whymper will later testify, Croz even lays aside his ice axe in order to help Hadow. But the Swiss and the Englishman cannot see exactly what is going on. Suddenly Hadow slips and falls against Croz. They are both falling downwards and their weight drags Reverend Hudson and Lord Douglas from their steps.

PD

Startled by Croz’ exclamation old Peter manages to quickly wrap the piece of rope between Whymper and himself around a rock. Since they share a rope with young Peter, the three men are able to hold themselves. But the thinner rope between old Peter and Lord Douglas breaks. The first four members of the rope team slide downwards and fall over an edge onto the Matterhorn Glacier 1,000 metres below. As Whymper later reports, there was nothing he and the Taugwalders could do save their lives.

THE QUESTIONS

Dismay, shock, bewilderment. Edward Whymper and the Taugwalders are unable to move for half an hour. Whymper later writes that the Taugwalders were shaking and paralysed with fear and cried like little children. During the painfully slow descent, the three are on constant lookout for the fallen and call them, but it is all in vain. At 9:30 p.m. the survivors reach the so-called shoulder, where they await the next morning. At 3:30 a.m. the next day, they continue to climb downwards. After a gruellingly long and silent walk they reach Zermatt. Now the people there learn at which steep price the victorious summit ascent they observed from the valley with binoculars was achieved.

Torn or Cut up?

Zermatt is divided: Many villagers think Peter Taugwalder is responsible for the tragedy. Others believe the 45-year-old is a hero, since it was his readiness of mind that saved not only his own life, but also those of his son and Whymper. But soon enviers, who begrudge Taugwalder’s fame of being the first Zermatt mountain guide to climb the “unclimbable mountain”, chime in. Rather quickly a rumor appears: “Taugwalder cut up the rope!”

The same day a search party spots three dead bodies on the glacier at the north face’s foot. The following day, a group including Whymper tries to reach the fallen at the foot of the Northface. The corpses of Michel Croz, Reverend Hudson and Douglas Hadow lie next to each other, still roped up. Lord Douglas, however, was never found.

The Italians on the Summit

Meanwhile Jean-Antoine Carrel and Jean-Baptiste Bich reach the Matterhorn’s summit – three days after the first ascent – climbing from the Italian side over the Lion ridge. For safety reasons two members of their rope party of four persons, Amé Gorret and Joseph-Augustine Meynet, stay back at the summit’s foot.

But the general attention remains focused on the fatal incident of the 14th of July: The question of guilt and responsibility is discussed everywhere. Six days after the return of the three survivors an inquiry commission of the Visp district court takes on the case and interrogates Peter Taugwalder and Edward Whymper at the Mont Cervin Hotel in Zermatt. When asked whether or not the rope between him and Douglas was strong enough, Taugwalder assures that he examined the three ropes before the ascent and approved of using them.

“If I had found the rope too weak, I would have recognised it as such before the ascent of the Matterhorn and I would have rejected it.”

As the court documents made available to the public in 1920 show, Whymper was not asked about the use of the ropes or any other touchy subjects. The interrogations are not very detailed. Finally the inquiry commission decides against opening criminal proceedings. They find no one to be guilty. Young Hadow is identified as “cause of the tragedy”. Was it merely a tragic accident?

Wild Theories

Not everyone believes so. The media start to report on the subject and publish different theories on the tragedy’s course of events. Who is responsible for the four lives lost at the Matterhorn’s first ascent on July 14th 1865? Mountain guide Peter Taugwalder, who held the rope in his hands when it ripped? Edward Whymper, who – despite not being a mountain guide – acted as leader of the party but failed to check the correct use of the ropes? Or had one of the three survivors really cut up the rope? The Austrian newspaper “Neue Freie Presse” offers an especially adventurous version: Whymper’s helping hand appeared behind an exhausted Taugwalder, who could no longer hold the fallen four, to sever the rope “with cold steel and clean cut”, they write. The Swiss print media, including the NZZ, is outraged by this “conscienceless scribbling”.

Power of Interpretation

Whymper soon addresses the public. On July 25th he writes a letter to one of the founders of the Swiss Alpine Club. There, he describes the events from his point of view and refuses to take responsibility.

“A single slip or a single false step, has been the cause of all this misery”

And: “I cannot but think, that had the rope been tight between those who fell as it was between me and Taugwalder, the whole of this frightful calamity might have been averted”. He never addresses the accusations of the Austrian newspaper.

In 1871, Whymper publishes “Scrambles Amongst the Alps”, his first book. In it, he advances his self-stylisation as the Matterhorn’s tragic hero, which he further develops in his subsequent work “The Ascent of the Matterhorn”. The Taugwalders have less access to the public – they probably cannot even read or write. They are thus forced to leave the interpretation of the events to the Briton.

The Curse of the Matterhorn

Over time Edward Whymper’s account of the events changes. More and more he paints the two Taugwalders as being weak and of questionable character. He suspects that Taugwalder senior used the weaker rope between himself and Douglas on purpose, to be able to safe himself and his son in case of a fall. For the Zermatt mountain guide, this accusation means character assassination.

The first ascent of the Matterhorn turns into a curse for Peter Taugwalder. He cannot make profit of the beginning tourist invasion: for a while, his off-putting depictions even prevent other Zermatt mountain guides from offering lucrative tours to the prestigious summit. Different sources indicate an increasing physical and mental decline. In 1871 he stops leading guided mountain tours. For a short while he even emigrates to the United States. He dies lonely and broken in his cottage at the Schwarzsee near Zermatt in 1888.

Whymper, too, is haunted by the Matterhorn tragedy for the rest of his life. The unanswered questions and suspicions never stop troubling him. Nevertheless, he is able to make profit of his fame and becomes the most renowned alpinist of his time. As such, he participates in expeditions to Greenland, South America and the Canadian Rocky Mountains. He gets married at 65 but separates from his wife four years later. He then retires to Chamonix, where he dies alone in a hotel room in 1911 at the age of 71.

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

The Myth

What really happened on July 14th 1865, will forever remain a mystery. After countless investigations lasting until recently, it cannot be ruled out that the rope was cut up, although it seems very improbable. The search for one single culprit is probably wrong altogether. The entire constellation of this summit attempt must be described as fatal. Instead of an experienced and well-prepared team a heterogeneous group of people acted overhasty. At no point in time, was it made clear, who was leading this expedition. The historical context should not be forgotten either: little was known about effective safety technologies for mountaineering or the correct handling of ropes.

The race to the Matterhorn's summit, which in one way or another ended tragically for all participants, benefited only one winner: Zermatt. It is needless to ask, whether this mountain would have become a myth, had its first ascent been without drama and unresolved questions. The Matterhorn is the ultimate Alpine summit, brand of Switzerland and a symbol of the glory and misery of mountaineering.

Facts and Figures

There are 48 four-thousand-metre mountains in the Swiss Alps. The Matterhorn on the border between Switzerland and Italy is one of them and the tenth highest mountain in Switzerland. The perfect pyramide is the most photographed mountain on earth, and casts its spell over many people all over the world.

Geo-Coordinates

7°39′30″E

Height of the Matterhorn

percent of all Zermatt-tourists are from Switzerland, 7,5 percent from Great Britain.

Every summer around

mountaineers climb the Matterhorn. On a beautiful summer day up to 200 mountaineers scale the mountain.

Every year

people die while scaling the Matterhorn. Around 500 climbers have died at the Matterhorn so far.

Including Lord Douglas until today

people, who fell down the Matterhorn, were never found.

people were rescued by helpers of Air Zermatt since 1980 until today.

of the rescues of Air Zermatt take place at the Hörnli ridge, 95 percent with a helicopter.

alpine guides of all ages in Zermatt frequently lead tourists to the Matterhorn's peak.

PD

PD.

-

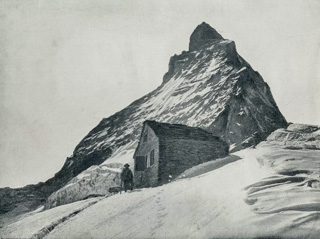

The Hörnli hut In 1880 the people of Zermatt erected a hut for up to 17 climbers on 3260 meters. The initiative for the construction was started by the Monte Rosa section of the Swiss Alpine Club (SAC).

-

The Berghaus Matterhorn In 1911 the community of Zermatt built the Berghaus Matterhorn (also called Belvedere) in close distance to the Hörnli hut. Until 1987 the Hörnli hut and the Berghaus at the Matterhorn were separate businesses. From then on the Berghaus' keeper was assigned for taking care of the Hörnli hut. In July 2015 the Hörnli hut will reopen after an extensive overhaul.

-

Fall is the most common reason of death at the Matterhorn. Other common death causes include freezing, rock fall and rapid weather changes according to Bruno Jelk from Air Zermatt.

-

Bruno Jelk has been leading Zermatt's mountain rescue team for more than 35 years. The alpine guide and skiing instructor has saved 600 mountaineers from the Matterhorn.

-

Kurt Lauber has been keeper of Hörnli hut since 1995. He is a man of many talents, being a skiing instructor, an alpine guide, helicopter pilot and a member of Zermatt's mountain rescue team.

-

Lucy Walker On July 22th 1871 Lucy Walker was the first woman to reach the Matterhorn's summit.

-

Richard Andenmatten climbed the Matterhorn over 800 times, this is a record.

-

Kevin Lauber is the youngest summiteer of the Matterhorn. The son of Hörnli hut keeper Kurt Lauber reached the mountain top for the first time at the age of eight. Ulrich Inderbinen climbed the Matterhorn 371 times. He reached the summit at the age of 90 for the last time.

-

Kilian Jornet holds the record for being the Matterhorn's fastest summiteer via Lion ridge. It only took him 1 hour 53 minutes to reach the mountain's peak, starting from Cervina, Italy. He broke the record of Italian Bruno Brunold by more than 15 minutes.

-

Dani Arnold is the fastest climber of the Matterhorn's northface. On 22. April 2015, he climbed the steep wall in 1 hour and 46 minutes.

-

Toblerone Swiss poster artist Emil Cardinaux created the most famous mountain shaped icon in the history of Swiss chocolate making during the 1920s: He depicted a pack of Toblerone chocolate hovering in front of the Matterhorn on a huge enamel sign.

-

Kiosk on the Hörnli ridge: What about a newsstand serving papers and refreshments on the Matterhorn? This idea did not occur to the likings of Mountain scaling legend Reinhold Messner. The expert climber could not really laugh at this, even after realizing that he got pranked by show master Kurt Felix («Verstehen Sie Spass?»).

Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

Colophon

Team

- Reported by

- Alexandra Kohler, Ruth Spitzenpfeil

- Edited by

- Susanna Rusterholz, Alexandra Kohler, Ruth Spitzenpfeil, Marvin Milatz

- Design and Development

- Benjamin Schudel, Simon Wimmer

- Photo editing

- Catharina Hanreich, Besiana Bandili

- Photographer

- Christoph Ruckstuhl

- Copy editor

- Yvonne Bettschen

- Translation

- Teresa Delgado

- Contributors

- Daniel Anker, Marc Lauper

- 3-D-Model

- Pix4D SA, pix4d.com

Sensefly sensefly.com

Sonja Betschart, Lisa Chen - Project leaders

- Alexandra Kohler, Benjamin Schudel

Sources

- Luisa und Beat Perren: Matterhorn. Climbing the Classic Routes. 2009

- Uli Auffermann: Das grosse Matterhorn Lexikon. 2014

- Alan Lyall: The First Descent of the Matterhorn. 1997

- Edward Whymper: Der lange Weg auf den Gipfel. 2005

- Georges Grosjean: Die Erstbesteigung des Matterhorns am 14. Juli 1865. Die Alpen / SAC. 1965

Contact

- storytelling@nzz.ch

- @nzzstorytelling